The Enduring Legacy of Amy Carmichael: A Life of Surrender

I can’t remember when I first heard of Amy Carmichael. Her life has made an indelible impression on mine—for her connection to my family generations ago, her tireless efforts to rescue children from temple prostitution, her sacrificial missionary work that inspired Elisabeth Elliot’s faith, and her deeply profound writing, borne out of suffering and pain.

When I was researching my heritage, I discovered that some members of my family in India were closely connected to the Dohnavur Fellowship at the time Amy Carmichael was ministering there. I was born in Chennai, not far from where Amy served. I’ll share more about that connection in my next post when I talk about heroes in my family’s past.

A Short Biography of Amy Carmichael: Her Life of Sacrifice and Service

Amy Carmichael (1867–1951) was born in Millisle, Northern Ireland, and raised in a devout Presbyterian home. After her father’s death when she was 18, financial hardship forced the family to move to Belfast and later to England. During a Keswick Convention, she sensed a call to missionary work but her initial application to the China Inland Mission was rejected due to poor health, including neuralgia—a painful nerve condition that often left her bedridden for weeks.

In 1893, she was accepted by the a missionary society and sent to Japan. After just over a year, ongoing health issues, attributed to the cold, damp weather forced her to return. In 1895, she sailed to India, where she would serve the rest of her life, more than 55 years, without ever returning home on furlough.

Amy first joined the mission station at Tinnevelly under the leadership of Rev. Thomas Walker and his wife. In 1898, while on an evangelism trip, Amy met a young girl named Preena who had been dedicated to temple service, which was then referred to as temple slavery, by her widowed mother. Amy took the girl in. Though it was three years before another child was brought to her, that moment opened her eyes to the reality of ritual exploitation and the profound need surrounding her.

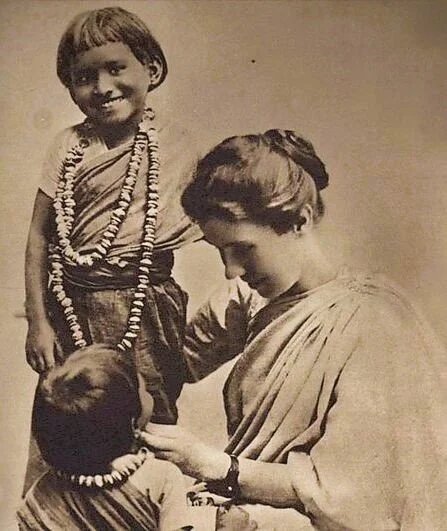

In 1901, when a five-year-old girl was rescued and entrusted to Amy’s care, she and the Walkers formally began what became known as the Dohnavur Fellowship, a ministry to care for children rescued from religiously sanctioned trafficking. Though Amy had originally wanted to be an itinerant evangelist, she surrendered to the slow, daily rhythms of caregiving—cleaning, teaching, discipling, even cutting the toenails of the children who called her “Amma,” which means mother in Tamil. She once wrote, “If by doing some work which the undiscerning consider 'not spiritual work' I can best help others, and I inwardly rebel, thinking it is the spiritual for which I crave, when in truth it is the interesting and exciting, then I know nothing of Calvary love.”

In 1931, a serious fall left Amy mostly bedridden for the final 20 years of her life. She rarely left her room and required assistance with even the simplest tasks. But Amy didn’t feel sorry for herself or wonder if she could still serve the kingdom. During those years, she wrote 14 of her 35 books, including most of her beloved works of poetry, biography, and reflections on suffering.

Amy Carmichael died in 1951 in India at the age of 83, after five decades of missionary service with the Dohnavur Fellowship. She requested no gravestone or monument. Instead, a simple birdbath marks the spot under a tree at Dohnavur, bearing just one word: Amma.

Amy Carmichael and the Devadasi System: Rescuing Children from Ritual Exploitation

Amy was heartbroken when she realized that young girls, some barely older than toddlers, were being dedicated to temples in a practice known as the devadasi system—a form of ritual sexual exploitation that forced them into lives of abuse under the guise of religious duty.

Amy took in these girls, gave them names and dignity, and offered not just shelter but long-term care in a Christ-centered community. She faced fierce opposition for intervening, yet she persisted, believing every child was worth the cost.

While others had spoken against these practices, Amy was one of the first missionaries to devote her life to rescuing victims and building an enduring alternative. In her lifetime, she helped rescue hundreds of children and her work helped pave the way for cultural and legal reform. In the region where Amy Carmichael ministered, the devadasi system was officially abolished and the ban enforced in January 1948, three years before her death.

How Elisabeth Elliot Carried Amy Carmichael’s Legacy Forward

Decades later, Elisabeth Elliot—another missionary—would bring Amy Carmichael’s life and words to a new generation. Elliot’s writing deeply shaped my own faith, and the first book I read as a new believer was her Shadow of the Almighty. She often quoted Amy and introduced many readers to her through A Chance to Die, the biography she wrote about Amy’s life. Elisabeth Elliot wrote in the preface of A Chance to Die, “Amy Carmichael became for me what some now call a role model. She was far more than that. She was my first spiritual mother. She showed me the shape of godliness.”

It was through Elisabeth Elliot that I first encountered two phrases from Amy Carmichael that have profoundly shaped my own walk:

“God knows all about the boats”

“In Acceptance Lies Peace”

God Knows All About the Boats

I first read this phrase in Elisabeth Elliot’s book Be Still My Soul. Amy, then a young missionary in Japan, was delayed for days when a scheduled boat never came. Worried about time and frustrated by the inconvenience to others, she was gently reminded by a seasoned missionary, “God knows all about the boats.”

That simple phrase became a lifelong anchor for Amy—and now for me as well. It’s a reminder that God knows every delay, every waiting room, every plan gone awry. Even when we wait without answers, we can trust that even this is part of God’s plan.

The Real Story Behind “In Acceptance Lies Peace”

“In acceptance lieth peace” is perhaps Amy’s most beloved phrase, taken from her poem by that name. I used to think Amy wrote it after her debilitating accident in 1931, but I’ve since realized it was penned earlier, in 1915, after the death of her dear friend Ponnammal. Ponnammal was a strong Christian and vital part of the ministry, a woman who worked tirelessly and faithfully alongside Amy, shouldering much of the load of Dohnavur. Amy said that the sorrow after her friend’s death led to “anxiety upon anxiety.” When others tried to comfort Amy with well-meaning words like “You’ll be given another Ponnammal,” she found them hollow. She reflected:

“Mistaken words, and vain. They did nothing to help us… No, it is not by giving us back what He has taken that our God teaches us His deepest lessons, but by patiently waiting beside us till we can say: I accept the will of my God is good and acceptable and perfect, for loss or for gain.” (Gold Cord)

This poem was written following that huge personal loss, reflecting Amy’s authenticity and deep faith:

In Acceptance Lieth Peace

He said, ‘I will forget the dying faces;

The empty places,

They shall be filled again.

O voices moaning deep within me, cease.’

But vain the word; vain, vain:

Not in forgetting lieth peace.

He said, ‘I will crowd action upon action,

The strife of faction

Shall stir me and sustain;

O tears that drown the fire of manhood cease.’

But vain the word; vain, vain:

Not in endeavour lieth peace.

He said, ‘I will withdraw me and be quiet,

Why meddle in life’s riot?

Shut be my door to pain.

Desire, thou dost befool me, thou shalt cease.’

But vain the word; vain, vain:

Not in aloofness lieth peace.

He said, ‘I will submit; I am defeated.

God hath depleted

My life of its rich gain.

O futile murmurings, why will ye not cease?’

But vain the word; vain, vain:

Not in submission lieth peace.

He said, ‘I will accept the breaking sorrow

Which God tomorrow

Will to His son explain.’

Then did the turmoil deep within me cease.

Not vain the word, not vain;

For in acceptance lieth peace.

As I learned the story behind this poem, it’s meant even more to me. People often try to explain suffering or rush us through grief. But Amy doesn’t suggest forgetting, striving, withdrawing, or resigning ourselves to defeat. She invites us to sit with sorrow, believing one day God will explain more to His children. But until then, peace comes through acceptance.

She later wrote that acceptance became one of their pivot words. It became, she said, “the warp and woof of the fabric of life.” Years later, she said that we won’t have “strength to resist the ravaging lion as he prowls about seeking whom he may devour, unless our hearts have learned to accept the unexplained in our own lives, and the delays and disappointments and reverses which often come where our prayer for others seems to fall into silence…” (Gold by Moonlight). Amy knew how it felt to have prayers go unanswered, especially for others, and yet to trust God with what she didn’t understand.

Gold by Moonlight: Amy’s Reflections on Suffering

Amy Carmichael’s Gold by Moonlight, published four years after she became disabled, is a raw and honest look at suffering. She writes in the preface:

“This book will not please any who have cut, dried, and labelled thoughts about suffering… Like Rose from Brier it has been written, not by the well to the ill to do them good, but by a fellow-toad under the harrow.”

Gold by Moonlight is a firsthand look at suffering, not a detached reflection. Amy understands the emotional and spiritual toll of long-term suffering as an invalid. She writes:

“The clouding of the inward man which often follows accident, or illness, may be like a very dark wood. It can be strangely dulling and subduing to wake up to another day that must be spent between walls and under a roof; and a body that is cumbered by little pains—pains too small to presume to knock at the door of heaven, but not too small to wish they might—can sadly cramp the soul, unless it finds a way entirely to forget itself.”

And this line truly took me aback:

“There are many rooms in the House of Pain. I have asked that I may not miss any room where a reader of this book is or shall be.”

Amy’s suffering was so intense and isolating that at times she longed for death. Yet she asked God not to spare her any pain if it meant helping others. That prayer is breathtaking. To be willing to suffer in order to meet others in their sorrow takes a kind of courage I aspire to have. But I am far from there.

Amy Carmichael’s Prayer of Fire: “Make Me Thy Fuel”

Amy Carmichael’s life was marked by radical surrender. She didn’t want comfort if it cost her closeness to Christ. Nor did she pursue safety or ease. She wanted to burn with holy passion, to be spent for Jesus. She captured that desire in what is perhaps her most quoted prayer, likely written in 1912, shortly after the death of her dear friend and mentor, Thomas Walker.

Make Me Thy Fuel

From prayer that asks that I may be

Sheltered from winds that beat on Thee,

From fearing when I should aspire,

From faltering when I should climb higher,

From silken self, O Captain, free

Thy soldier who would follow Thee.

From subtle love of softening things,

From easy choices, weakenings,

(Not thus are spirits fortified,

Not this way went the Crucified,)

From all that dims Thy Calvary,

O Lamb of God, deliver me.

Give me the love that leads the way,

The faith that nothing can dismay

The hope no disappointments tire

The passion that will burn like fire,

Let me not sink to be a clod:

Make me Thy fuel, Flame of God.

Amy Carmichael’s passion still ignites hearts today. Her life and words invite us not merely to admire her, but to follow Christ as she did—without reservation. May her prayer become ours as well.